Happy Monday and welcome back to Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

As I promised last week, from today until November 1 I am going to publish all the premium content for free. In a slight change of schedule I am moving the news briefing to tomorrow, because I really wanted you to have today’s story first.

A reminder that it’s now more important than ever to reach a big number of readers - both because your feedback will help shape my membership offer, and because the more members I have, the more time I can spend working on Lights On.

So please share and talk to your friends about it!

Scientist Kyu Taek Cho observes the behavior of a flow battery's chemistry. Image credit: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

To meet the Paris Agreement goals and keep global warming well below 2C above pre-industrial levels, the world needs a radical overhaul of its energy system - but countries still need to figure out how to fill the technology gap that would get them there. We hear about the cost of renewable energy going down year on year, and that’s often seen as definitive proof that a global energy transition is underway, and unstoppable.

But low cost doesn’t always guarantee that a technology will be easy to deploy at scale - energy systems are more complex than that. So why do different technologies progress at different speeds? And what can we do about that?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has designed a scenario to illustrate what it would take for a 66 percent chance to keep global temperatures at around 1.8C. Under this scenario, global CO2 emissions fall from 33 billion tonnes in 2018 to less than 10 billion tonnes by 2050, and are on track to reach net zero by 2070. The bad news is that over a third of the emission reduction needed to achieve this goal comes from technologies that are still in prototype phase, and won’t be available at scale without further research and development (R&D).

Cheap tech is not enough

Bridging that gap is not only a question of reducing cost. To be scalable, a technology needs to be cheap, but also easily replicable in different locations and countries with unique economies and regulations.

“On one hand, you have solar PV, which has undergone spectacular cost reductions, has a global market and gets deployed pretty much everywhere with minimal adaptation,” says Abhishek Malhotra, energy policy expert at IIT Delhi and author of a new paper on how to accelerate low carbon innovation.

“But then the opposite end of the spectrum is biomass power, which was seen as a very promising technology just a decade ago.” If you looked at projections from that time, Malhotra says, biomass was expected to play a huge role in terms of decarbonisation of the energy sector. But looking back, it has not fulfilled its potential. Biomass technologies are not easy to replicate, Malhotra explains, because the design of each plant varies depending on the biomass feedstock it can process.

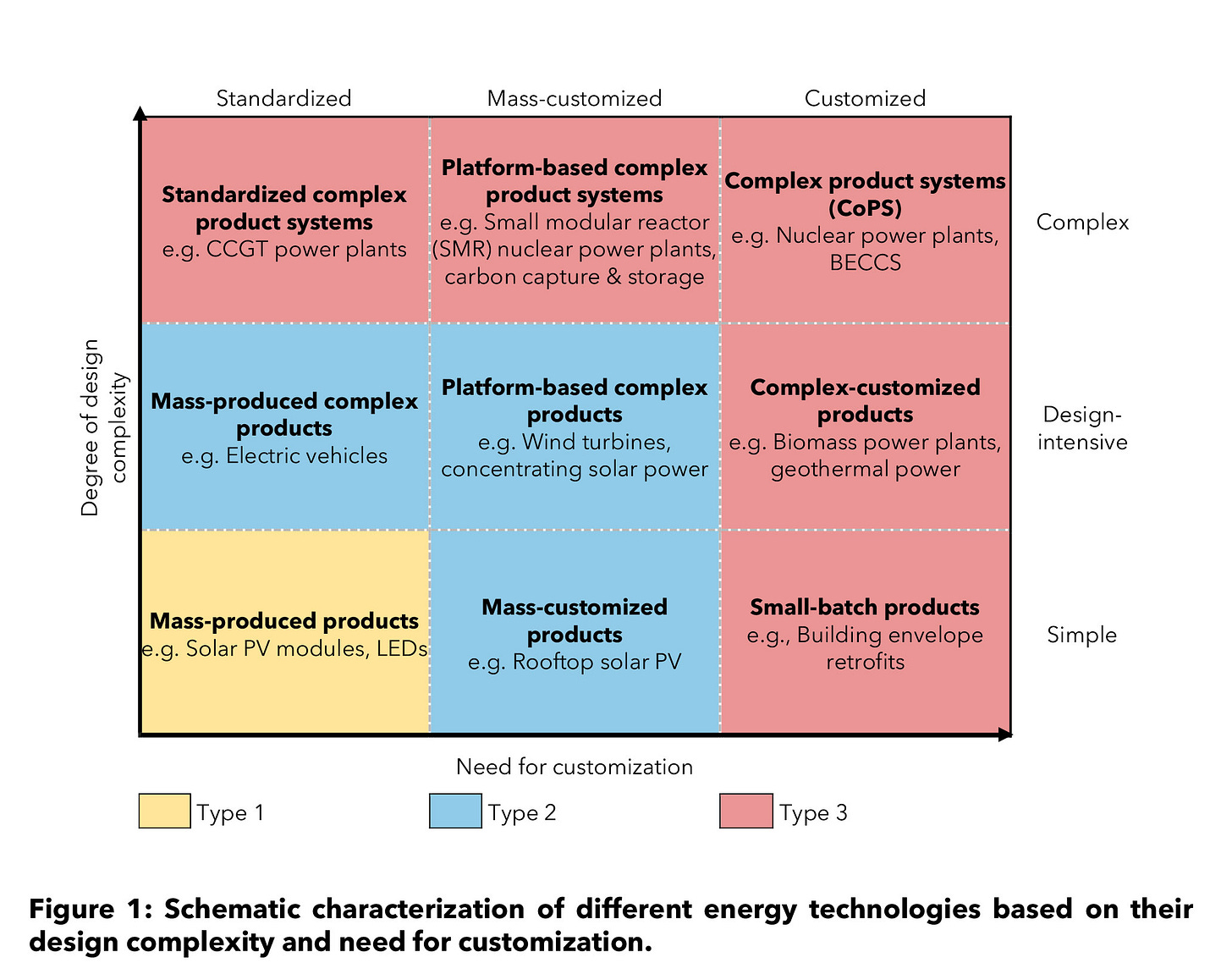

The study, published today in the journal Joule, organises the main technologies essential to a global energy transition according to their design complexity and need for customisation. For example, photovoltaic is both simple and very standardised, which means many players can start producing solar panels quickly. This in turn fosters competition, and eventually creates the right environment for innovation.

Image courtesy of Abhishek Malhotra

On the other hand, nuclear power plants and BECCS (bio-energy with carbon capture and storage) systems are both very complex to design and need to be customised to the specific environment they operate in. Unfortunately, these hard-to-scale technologies are as essential to the Paris Agreement as solar or wind.

The Paris Agreement relies heavily on national green industrial policies to drive clean energy innovation, although it encourages international cooperation in other areas such as emission trading. The authors argue that this approach is not going to work if we want to accelerate the development pace of technologies like nuclear, carbon capture and storage or lithium ion batteries: international cooperation is essential to help standardise design, development and regulations across countries.

India’s energy transition

There is no doubt that India is hard at work to meet its ambitious climate targets, and is mainly focussing on the low hanging fruit of the energy technology spectrum - wind and large solar.

But other technologies such as batteries, which are more complex to design but could be easily standardised, or rooftop solar systems, which are easy to design but require a bit more customisation, remain an untapped opportunity.

“We need to change the narrative around these technologies, and see them as opportunities rather than as costs,” says Malhotra. “At some point, we will have to transition away from resources we are heavily dependent on, such as coal,” and solar alone can’t meet India’s booming and diverse energy needs.

Policymakers and industry leaders are still in denial about coal still being relevant after 2050, says Aniruddha Bhattacharjee, a senior researcher at the consultancy Climate Trends in Delhi. “But simple technologies such as wind and solar are not only better suited to the Paris Agreement’s goals, they are also more competitive.”

Electricity demand in India is only going to grow, Bhattacharjee says, because the government has this huge ambition of going from a $1 to a $5 trillion economy. “You are growing the economy by five times, and the power required is probably 20 times. So, yes we need a lot of power, but simply based on economics, it's complex technologies that will be phased out.”

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter and you’d like to read it every week, you can subscribe below. Tip: if you add my address to your contacts, this email won’t end up in the spam or promotions folder!