Welcome to today’s Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

As usual if you have suggestions, stories you would like me to cover in 2021, tips or feedback on how to improve my work, I’d love to hear from you. You can reply to this email or leave a comment at the bottom.

And if you want to support Lights On, you can become a member for $7 a month or $70 a year. Students get 60 percent off forever.

If we try to imagine what India’s climate and energy conversation will look like this new year, some things are sure to be on the menu. Solar expansion is one, with more hybrid projects combining a range of sources to increase the reliability of India’s electricity supply. Hydrogen is poised to become more mainstream, as part of a drive to decarbonise manufacturing. We’ll also be waiting for a possible (aspirational) pathway towards net zero which may or may not materialise at the next climate talks in Glasgow.

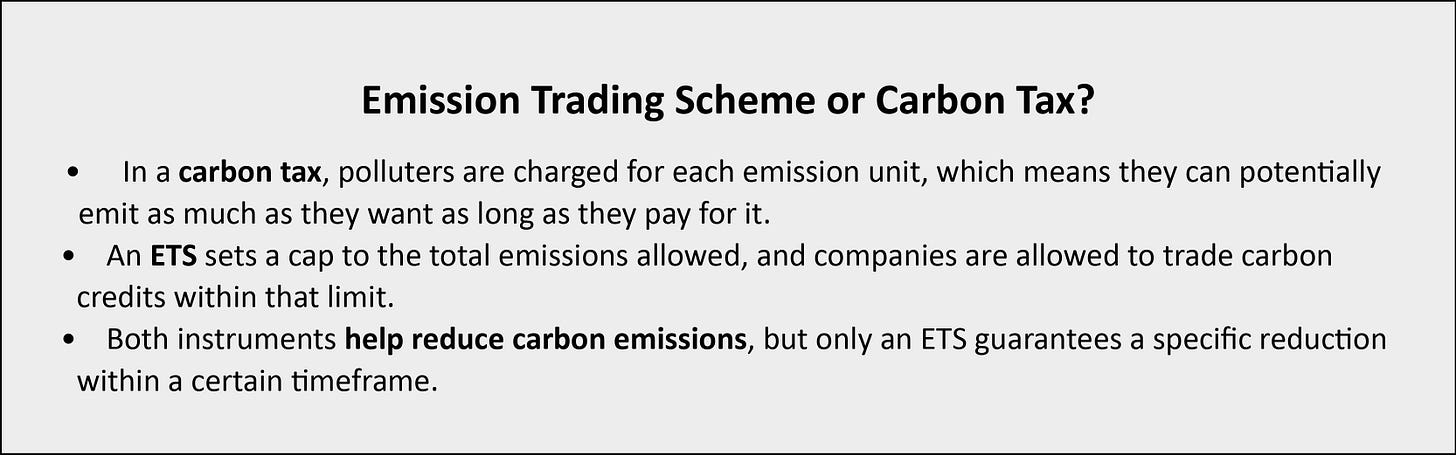

Other actions may have fallen under the radar until now, but are no less essential to India’s climate goals, and perhaps more importantly to its domestic ambitions. Carbon markets, also known as emission trading schemes (ETS) are one such example.

Putting a cap on carbon emissions would help India decarbonise its economy at the pace required to meet and possibly overshoot its climate goals, which some experts say are unambitious. But reducing emissions from local industries also means cleaner air and better health for Indians - a problem that the coronavirus put in sharp focus last year.

At the moment, India’s pledge under the Paris Agreement doesn’t mention a reduction in emissions. Instead it opts for a decrease of its carbon ‘intensity’, which means its carbon footprint will keep rising, but at a slower pace relative to GDP growth. If India’s pledges are currently ‘2 degrees compatible’ according to the research project Carbon Tracker, its booming economy - which is expected to forcefully bounce back after the Covid crisis - could yet put the country on a carbon intensive path.

And the government is taking notice. A detail tucked away in a recent policy document, the outline of the Apex Committee for Implementation of Paris Agreement (AIPA), reveals for the first time that a comprehensive carbon market might be on the cards.

At the moment, India has two market trading systems, the Renewable Energy Certificates (REC) and Perform Achieve and Trade (PAT), which are designed to reduce emission intensity rather than absolute emission levels. The two schemes allow you to purchase and sell carbon credits, but you can’t exchange your credits between both markets. In other words, they are not ‘linked’, which means that a comprehensive national carbon market is still a very distant prospect.

This gap is “keenly felt” by Indian industries who would like to see more structure to guide their green initiatives, says Tamiksha Singh, a research fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in Delhi. Linking the two existing systems would be pretty hard for logistic reasons, Singh explains. Plus, translating the existing emission certificates into measurable carbon units would require much greater monitoring capacity than what is currently available.

But the time feels right. Vivek Adhia, India country director with the non profit Institute for Sustainable Communities, says that “a two to five year timeline” for the initiation of a national carbon market for India “seems to be quite realistic”. Of course, he says, the success of such an ambitious experiment will depend on whether it’s able to incorporate the diverse elements of India’s emissions landscape - including carbon-heavy sectors like steel, automobiles, textiles, chemicals and more.

In India a patchwork of small and medium businesses make up a big percentage of the national total emissions, and they are difficult to capture. Not many carbon markets look at small emitters, but India has been experimenting with how to incorporate small businesses into its carbon market plans in previous pilots, Adhia says. This could be done by targeting the small industries spread across industrial clusters at a regional level first, he explains.

“Even when the national regulation is not there, regional schemes are a good way to bring the small emitters on board because they are geographically grouped together,” he says.

Vaibhav Chaturvedi, economist with the Council on Energy Environment and Water who works on low carbon pathways, believes that India can build on the PAT scheme and deliver the architecture for a national carbon market in about five years. “The entities that are going to participate are, in all probability, going to be exactly the same,” he explains. “This is a very good thing because you already have a list of participants, and a lot of administrative ground is already covered.” This would make it easier to convert the existing scheme into a fully fledged emission trading program.

Leaping from experimental schemes to a robust national carbon market is not going to be a one-year affair. It’s something that the European Union tried in 2005 and botched, for example. China is expected to kick off its own ETS, which was due to start in 2020, early this year - it’s been three years and counting since the scheme was announced. India’s national plan is likely to rolled out in only a few selected sectors at first, similarly to China’s, and it will take a long time for it to expand to the whole patchwork of domestic industries.

But as India looks at the upcoming climate talks in November, where countries will ramp up their ambitions under the Paris Agreement, engaging in a potential carbon market plan, even on a theoretical level, would demonstrate international commitment as well as cater to the needs of a growing domestic industry looking to decarbonise.

That’s all for today! If you like what you read, please consider signing up for free or as a member: