Welcome to today’s Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

As always, if you want to know more about today’s post, just reply to this email and hit me with your burning questions. In case you missed last week’s stories, catch up with pollution scientist Pallavi Pant on why tackling pollution by shutting down the economy is a bad idea, and what India’s decision to pull out of the world’s biggest trade deal means for the green economy.

And if you are not a member, please consider supporting one of the very few sources of climate and energy news putting India and South Asia under the global spotlight.

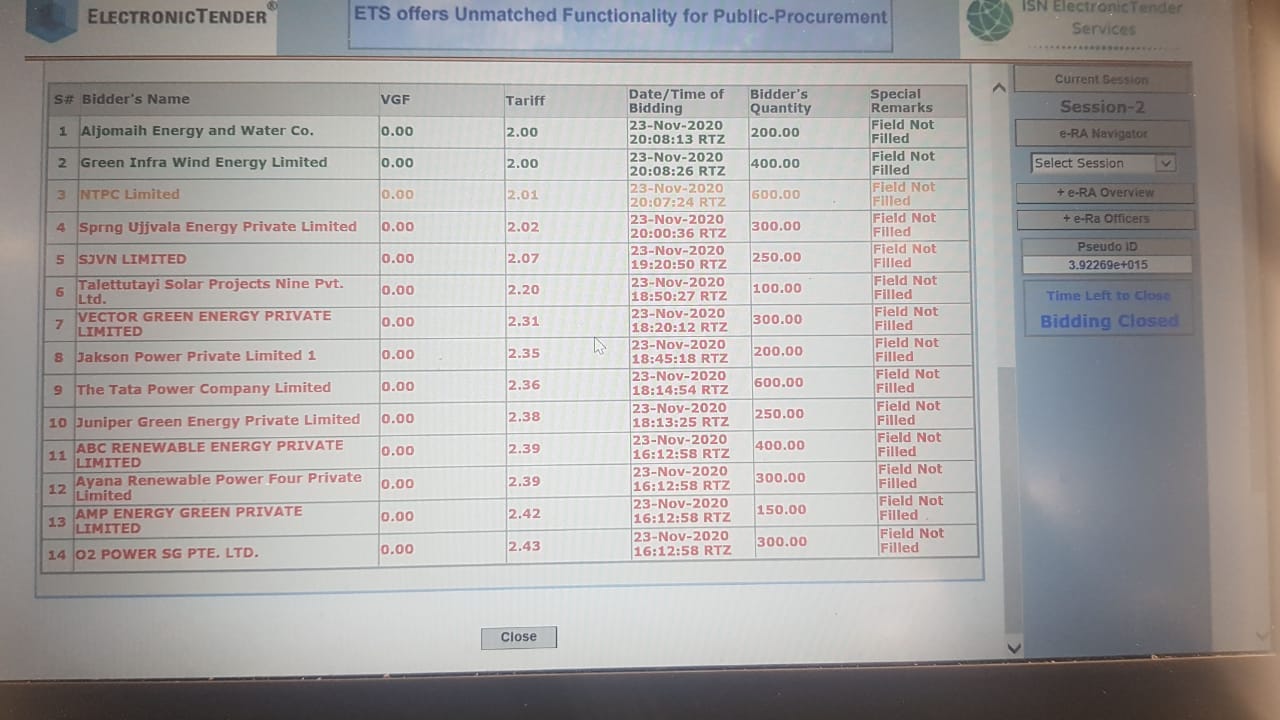

Despite a Covid-led slump, solar prices have hit a new low in India, already home to some of the world’s cheapest solar power. Earlier this week, two foreign developers promised to bring solar energy prices down to 2 rupees, or $0.027, per kilowatt hour (kWh), beating the previous record of 2.36 rupees/kWh ($0.032).

As part of an auction organised by the government owned Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) to assign 1070 MW of solar development in the arid state of Rajasthan, Saudi Arabia’s Aljomaih Energy and Water and the Indian branch of the Singapore-based Sembcorp bagged contracts for the construction of 200 and 400 MW of solar respectively.

If this sounds like an unstoppable ‘race to the bottom’, it’s worth remembering that the story of Indian solar is rife with false steps and broken promises.

A troubled love affair with solar energy

In 2018, the developer ACME quoted 2.44 rupees/kWh ($0.033) for a 600 MW development, a record that amazed the industry at a time when prices hovered between 2.50 and 2.87/kWh ($0.034 - 0.039). Not so long after, the company backtracked on its promise, citing Covid hardships. More recently, a ‘landmark’ $6 billion deal for the development of 8GW of solar capacity sealed in June by the energy giant Adani and SECI has reportedly failed to secure any customers.

A trade war with China, which still produces well over 80 percent of India’s PV modules, had the whole solar community worried that new basic custom duties on imports, combined with the existing safeguard duties, may tanker solar growth for good.

India has also set impossibly high targets for its solar development, and they will not be met without taking advantage of cheap technologies coming from abroad. It’s safe to say that the much touted 100GW of grid connected capacity by 2022 is now out of reach, as India had installed just 34.6GW as of March 2020. The next goal of 450GW of installed renewable capacity is still within reach, experts say, but not without major efforts. At stake is the country’s energy transition but also its international credibility, particularly after Prime Minister Modi reiterated his commitments in front of the G20.

Behind low prices

Falling prices are not necessarily a solid indicator of the health of India’s solar industry. Earlier this year, Vibhuti Garg, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, had warned that “any solar tariff below Rs 2.50 ($0.034) per kWh in the current market conditions in India is unsustainable. Winning should lead to the delivery of projects. Or else instances such as the cancellation of projects by ACME Solar with a tariff as low as Rs 2.40 per kWh [...] set a bad precedent”.

But this time, things may be different. A number of new factors are coming together making such low prices more realistic. First, more foreign investors are betting on India’s solar. They come with easier access to capital and low interest rates, which allows them to invest with more confidence. “They feel that the Indian markets are less risky, and they are pumping a lot of money,” Garg says. “Plus, interest related costs have a significant impact on the tariffs.”

Geopolitical factors also matter. “Consider Rajasthan as a hot spot for cheap solar tenders,” says Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO of the National Solar Energy Federation of India. Because it’s an arid region, he says, “a lot of it is not used for agriculture or commercial activities, so land is available at a lower price” and its acquisition doesn’t displace local communities. Its transmission system, including lines that connect with other states, is also particularly robust, Pulipaka says, which means that developers won’t struggle too much to create an efficient distribution network for their energy.

Modi caught in the middle

India is also currently enjoying a brief respite from a punitive fiscal regime that drives up the cost of solar panels. The 15 percent safeguard duties against Chinese imports will expire in July 2021, likely before the projects’ beginning, and despite promising new basic custom duties against China, the government keeps postponing their enforcement. New restrictions that will require investors to apply to enter the list of approved manufacturers are still not in place. “So this tender is shielded from all these three,” Pulipaka says.

The stars may have aligned for Indian solar, but these favourable conditions may change once the aggressive custom duties the government is planning kick in. Then tariffs will inevitably go up again. “I think that the government wants to achieve the 175 GW of renewable target,” Garg says, or at least end the race to 2022 as close as possible. “They are bidding out as many projects as they can before the basic custom duties come into force, so they will have an active pipeline”.

Ultimately, Prime Minister Modi will need to strike a balance between the needs of India’s solar makers and his Paris Agreement targets. If India keeps its promises to local manufacturers, who still can’t compete with Chinese products, and cracks down on imports, this week’s record low tariffs will likely remain a fortuitous one off.

That’s all for today! If you like what you read, please consider becoming a member and support the hard work that keeps Lights On truly independent: