Nepal's strategic role in India and China's energy tussle

And how the geopolitical challenge can become a force for good

Welcome to today’s Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

If you are not a subscriber, you can sign up below, for free, or you can support my work by purchasing a membership:

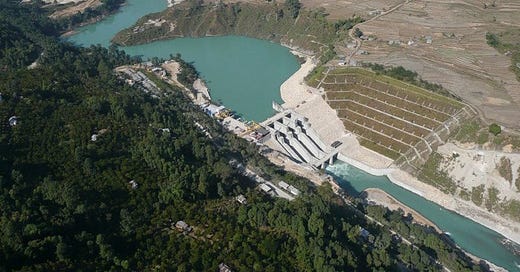

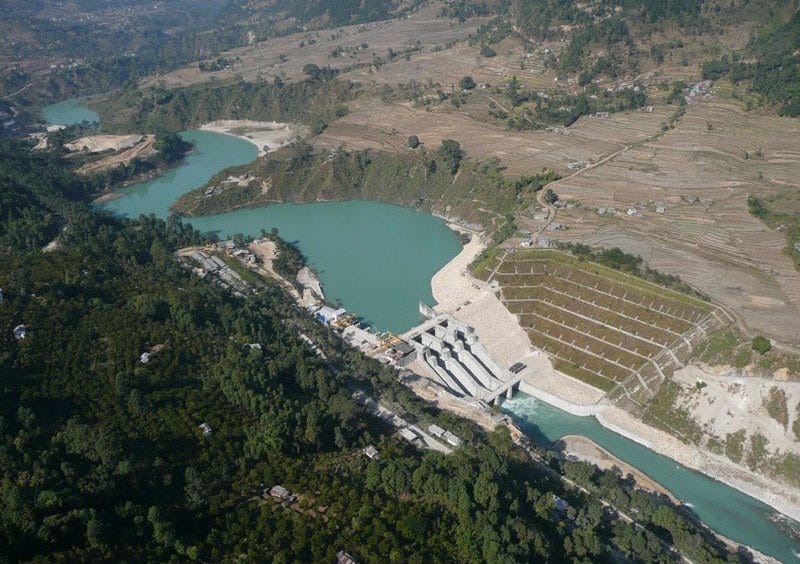

Nestled between China and India, Nepal is preparing for a hydropower boom. But while it builds the infrastructure to meet its own energy needs, it’s not necessarily becoming more independent from foreign influence.

Its two powerful neighbours are increasingly playing a part in Nepal’s energy story. China and India are providing finance to pay for the construction of big dams, setting up cross border power trading agreements, and expressing some of their animosity towards each other in the process.

“As of now, Nepal produces around 1.3GW of power, but the pipeline is quite promising, it will likely grow exponentially,” says Sagar Prasai, independent water and energy analyst based in Nepal. By the end of 2021, he says, Nepal is likely to hit around 2GW, and by 2022 it could reach up to 2.6GW. “We are doubling capacity in just two years. Back in 2008, we were at around 600MW. So, the first time around it took 12 years to double capacity.”

In 2000, 81 percent of Nepal’s 28 million population lived without electricity. Today it’s just 6 percent. But at this speed of development, Nepalis will not know what to do with all the extra power.

The Nepal Electricity Authority started exploring cross border transmission with neighbouring India three years ago. This year it concluded that the positive trading relationship with India

Reflects the sign of the country’s readiness for a spectacular transformation from the age of a devastating power deficit to an economy-stimulating power surplus.

India’s eyes on Nepal

On its side, India is keen to boost regional power flows. The government recently set up a high level group under the Ministry of External Affairs, supporting the creation of a regional power grid and market, which would include neighbouring Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka. This makes sense from an energy security perspective as countries in South Asia could reduce their dependence on fuel imports from less friendly nations such as Saudi Arabia. But also strengthens India’s stand in the region against Chinese influence, which through the Belt and Road Initiative extends across the region and beyond.

Earlier this month, the Indian government issued new detailed procedures for the import/export of electricity between India and countries with whom it shares borders. A paragraph tucked in the document reveals India’s belligerent stance. It says that Indian consumers can import energy from neighbouring nations

“provided that the generating company is not owned, directly or indirectly by any natural/ legal personality(ies) whose effective control or source of funds or residence of beneficial owner, is situated in/ citizen of a third country with whom India shares a land border”

“The geopolitical logic underpinning the rules is quite clear,” says Aditya Valiathan-Pillai, climate policy expert with the Center for Policy Research in Delhi. By putting ownership restrictions on who can sell into the Indian market and who can use the Indian grid to sell to a third country, “it attempts to keep investments from China out of the power systems of India's neighbours and thus out of the South Asian energy market.”

The approach, Valiathan-Pillai says, is amplified and made more urgent by recent tensions with China, its growing influence in South Asia, and a strategic focus on reducing the power system's dependence on China.

“They just want Nepali companies to furnish all the details as to where the investments are coming from, and that exposes potential risk for investors,” says Prasai. “Because as long as you maintain a case by case approval basis, it’s not a true market.”

China’s agenda

On the face of it, China is not the most obvious trading partner for Nepal. It doesn’t have a soft power base in the country - unlike India with which it shares the same religion, culture, even Bollywood movies.

But China has a presence in Nepal and is acquiring licences for hydropower plants that hold unique advantages. “China is trying to get a stake in some of the storage types,” Prasai explains. These are the plants that come with huge reservoirs, “and because they have a lot of water behind the dam, they can sell electricity in lean seasons, which has higher price than during the wet season” when those capturing river waterflow struggle because of lack of water.

China is currently the highest foreign direct investor in Nepal, Prasai says. The Chinese are trying to expand their influence by injecting cash in various sectors of the economy, but the move also makes economic sense “because these state owned companies have exhausted the Chinese market so they need to globally expand.”

Neither China or India are desperate for Nepalese hydroelectricity. China is a surplus country with some of the world’s most advanced renewable technologies and vast manufacturing hubs. India will make good use of clean hydropower energy to stabilise the grid as it integrates more renewables and faces intermittency issues, but for now the Covid crisis has slowed down energy demand. The most likely beneficiary of Nepal’s hydropower boom, Prasai says, will be Bangladesh, which is growing steadily and weaning off coal at a rapid pace.

“Like all great powers, China's actions arise out of its interests, which include economic diplomacy as well as security considerations,” says Ravi Bhoothalingam, a management consultant and an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Chinese Studies in Delhi. “Both these aspects are of special importance when China deals with those countries which border its sensitive ethnic-minority regions such as Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, where China considers 'stability' to be all-important.” Nepal falls into this category, where economic development is only half of the story.

However, Bhoothalingam says, small countries like Nepal have the power to play a constructive role. Rather than stoke rivalry, Nepal “can suggest some joint initiatives between Nepal, China and India.” It’s not easy for Nepal to orchestrate such moves, he adds, but it is possible.

And if the joint projects have a focus on common challenges such as green energy, sustainable mountain area development or watershed management, they would have benefits for the entire Himalayan ecosystem.

That’s all for today! If you like what you read, please consider signing up for free or as a member: