The untold energy story of India's protesting farmers

And how the Green Revolution is backfiring

Welcome to today’s Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

Last week I spoke with the World Bank’s energy specialist Amit Jain about India’s vision for a global clean grid - I recommend you check it out as you may soon hear more about it, now that the project is finally going ahead after it was delayed by the pandemic.

As usual, here’s your reminder that if you want to support Lights On, you can become a member for $7 a month or $70 a year. Students get 60 percent off forever.

Braving the November cold, tens of thousands of farmers marched on India’s capital. They set up camp on the outskirts of Delhi and haven’t moved since. The farmers, mostly from the northern states of Haryana and Punjab, demand that the government repeals a new law, passed on September 27, which introduces market reforms on the sale of rice, wheat and other crops. Over weeks and months negotiations with the government stalled, and the protests escalated when a fringe group of farmers stormed the city’s iconic Red Fort on Republic Day.

As of today, unrest continues in Delhi with no end in sight. Before the bill was introduced, farmers used to sell their produce to the government at a fixed ‘minimum support price’, as part of India’s push to feed its poorest. Now farmers, many of whom are chronically saddled by debt, fear that this decades-old provision may be withdrawn, at a time when government support is needed more than ever to withstand the impacts of increasingly low productivity.

Speaking with journalist Astha Rajvanshi, Punjabi farmer Singh Dhaliwal voiced the main concern on every protester’s mind, faced with a law which encourages private buyers to compete for the best price: “Whether it’s wheat or rice, we won’t be able to sell for our (usual) price when the big corporations come and the market is overcrowded with options.”

The Green Revolution

Farmers and the government do agree on one thing - that the agricultural system in India’s ‘bread basket’, as Punjab and Haryana are known, is broken, and water and energy are at the core of the problem.

“The problem starts with the advent of the Green Revolution in the mid 1960s,” says Ranjit Singh Ghuman, Professor of Eminence in Economics at Guru Nanak Dev University in Amritsar, in Punjab. “At the time the focus was on growing more food grains [to tackle hunger in the country], and wheat and paddy came very handy.” Punjab was chosen for that purpose due to its favourable climate, and the government spared no effort to encourage farmers to take up rice and wheat cultivation, offering high yield varieties, a steady supply of chemical fertilisers, fixed prices for the produce and free electricity to pump underground water for irrigation.

Fifty years later, farmers have delivered and are now specialised in the cultivation of the two crops, which are sown and harvested in rotation. “In 1971, only 9 percent of the net sown area of Punjab was paddy,” Ghuman says, “but now, the issue is that more than 75 percent of net sown area is under paddy.” In Punjab there is simply not enough water for that much rice, a crop that grows in flooded fields and requires - when cultivated with the traditional method - 15,000 cubic metres of water per hectare.

From 1996 to 2016, Ghuman says, the water table has gone down from a depth of 6 metres to 22 metres in the districts where paddy is cultivated. From 200,000 borewells in 1971, Punjab’s fields are now punctured with more than 1.4 million deep holes reaching for water. The situation, Ghuman says, has also put pressure on the energy system, because to extract water from such a deep water table you need to use more energy.

The energy and water nexus

Currently, the increasing costs are borne by local industries that pay a premium to support free electricity for the agricultural sector, and because farmers are a key voter pool local politicians are reluctant to change the rules. “This has completely distorted the entire electricity sector,” says Debajit Palit, a director for Rural Energy with The Energy and Resources Institute in Delhi. “Industries are paying up to eight rupees per kilowatt hour, where the farmers are paying about one rupee per kilowatt hour on average,” he says. “They are completely subsidising the agricultural sector, and soon they will reach a [sustainability] peak. Now if industries are not able to cover another price increase, then who is going to pay the [farming] subsidies?”

Palit says that one way of solving the problem would be to put a cap on free electricity for farmers, to encourage them to use energy more efficiently. But with underground water running out, this can only be a temporary solution.

“I think it's high time that Punjab shifts from paddy cultivation,” Palit says. As well as the water problem, he adds, “the soil is completely ruined” because of the intensive use of fertilisers, which contaminate the aquifers that are a source of drinking water. Experts agree that moving away from water intensive crops that were never meant for the local environment is the only way to avoid an environmental catastrophe and a mounting energy crisis - with the potential to exacerbate unrest among farmers.

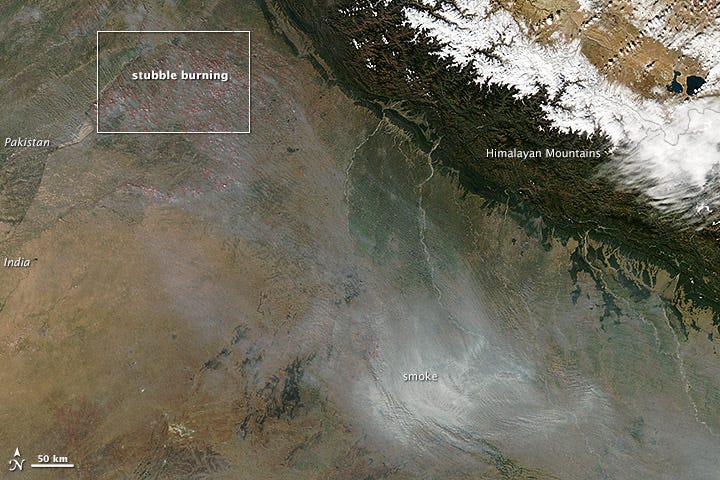

Pulses, millet and maize are some of the crops better suited to the local environment that could be sold at higher prices once cultivation picks up. Switching from the paddy-wheat combination would also solve the long term issue of stubble burning, which farmers use to clear the fields quickly between growing seasons, leading to severe air pollution in the Delhi area.

“For about one or two years, [farmers] might have to change their way of cropping,” Palit says. “They might have to learn new things, but then the benefits would start to show.” He believes that by opening up agricultural markets to the private sector, the new law could encourage farmers to choose more lucrative crops, and could be instrumental to easing the region’s impending water and energy crisis.

A just solution

But to place the onus of such a huge agricultural shift squarely on the farmers, after the government has created and supported an artificial ecosystem for five decades, would be “altogether wrong,” Ghuman says. If the new law were to do away with the Agricultural Produce Market Committee, a platform that safeguards the interests of farmers, and dismantle minimum support prices - as farmers fear it will, despite the government’s assurances – they would have to consider crop diversification, Ghuman concedes. But that would be twisting the farmers’ arm and it would be unjust, he says.

Instead, he says, the government needs to roll out the same policy mix it used to encourage wheat and paddy farming during the Green Revolution. “You will need to hand-hold farmers, provide a minimum support price, invest in research and development to create high yielding varieties and put in place public procurement to guarantee net income.”

Farmers have made it clear that the current standoff won’t end unless the government repeals the proposed bill, but what would replace it remains an open question - and could solve or worsen India’s impending farming and energy crisis.

That’s all for today! If you like what you read, please consider signing up for free or as a member: