Welcome to Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

A big thank you to my new subscribers - your support here and in person means the world, so please keep emailing, or chat with me on LinkedIn and Twitter.

We are just over *one week away* from November, when I will officially put up a paywall on most of my work. Please know that I really care about making what I do as accessible as possible - students get full access for $28 per year, and for every 100 subscriptions, I am offering 10 for free.

If you decide to become a member, your money doesn’t just pay for my work, but helps keep this project alive in the long term for many others too. So if you can afford it, consider becoming a founding member, and I promise it will be worth it. Otherwise, grab your 20 percent discount until November 1.

Thank you!

Delhi landscape during pollution season - Image credit: Flickr/thejuniorpartner

Untangling the soup of toxic chemicals in the air that makes Delhiites sick year after year is a feat that science has yet to nail. What we know and can measure with increasing precision are the frightening impacts on human health.

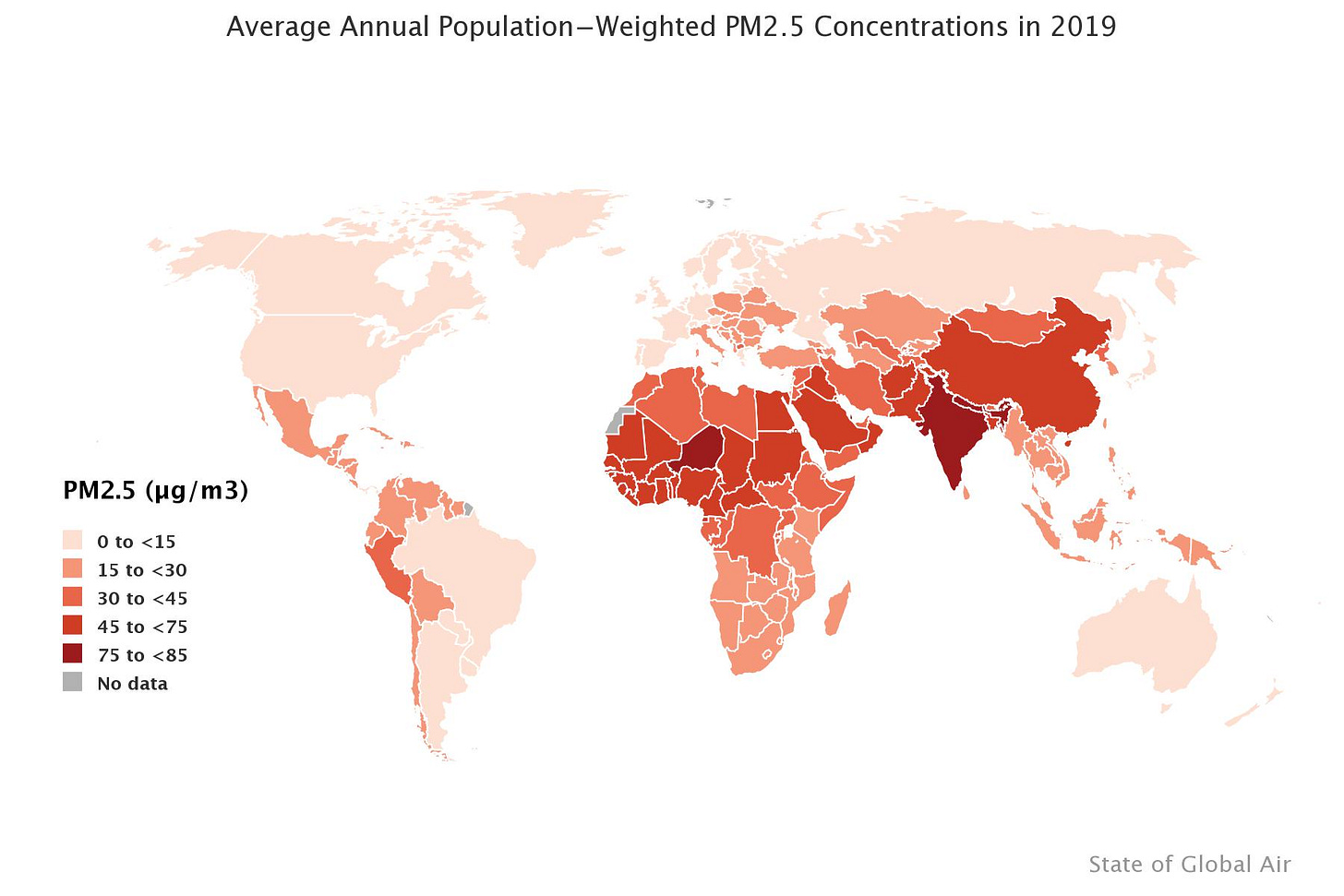

The new State of Global Air Report calculates that in India, in 2019 alone, breathing polluted air contributed to over 1.67 million deaths from stroke, heart attack, diabetes, lung cancer and other respiratory diseases. In the same year, an estimated 116,000 Indian infants lost their lives, due to conditions exacerbated by air pollution exposure.

Image credit - State of Global Air

And while the central government and the states squabble over who and what is responsible for the latest wave of bad air, the pollution emergency in Delhi compounds another chronic crisis that is often forgotten in the noise - the mountain of waste that risks taking over the city, or choke it with toxic emissions when burned.

The latest inspection from India’s pollution watchdog, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), flagged illegal levels of PM2.5, PM10, furans and dioxin at one of the main waste processing plants, situated at the heart of the city in the Okhla area. Furans are highly toxic pollutants that can affect the brain, skin, reproductive system and predisposition to cancer. PM10 and PM2.5 are particles that lodge in the lungs and in their fine form can enter the bloodstream affecting the whole body, including the heart.

While these findings come at the worst possible time, when Delhi battles the annual pollution spike which in turn exacerbates the coronavirus epidemic, they are just the tip of the iceberg.

Delhi is home to three waste to energy plants, set up in the Okhla, Bawana and Ghazipur areas over the past ten years when it became clear that the city’s landfill could not sustain the growing influx of unsegregated garbage - according to the latest available estimates, 8700 tonnes of waste per day in 2015-16 (and likely to have grown massively over the past five years).

The idea is to incinerate waste and use the heat generated in the process to produce energy. Countries such as Germany, Sweden and Norway employ this technology successfully, giving hope that waste to energy could help solve India’s waste woes.

While civil society group opposed the establishment of the plant since day one, and successfully sued its management which was forced to implement emission reduction equipment, the Okhla plant continues to receive carbon credits under the UN Clean Development Mechanism for its contribution “in improving the environmental condition in the city of Delhi by hygienic treatment of municipal solid waste resulting in improvement of health standard in the city”.

Delhi is the ideal setting for such large scale facilities, says a senior engineer who was involved in the design of the waste to energy plants, speaking on condition of anonymity. There is limited land to create landfills, and if run well, the plants can work at full capacity, catering to the needs of tens of millions. But red tape, poor quality of the waste, and a bidding process that encourages companies to promise unrealistically low prices mean that environmental impacts are often ignored.

“If you look at Delhi's waste, it’s highly organic,” says Sahadat Hossain, director of the Solid Waste Institute for Sustainability at the university of Texas Arlington. “And there’s also a lot of ash from street sweeping. All of that doesn’t burn well.”

Imagine any piece of cloth, Hossain says. If you try to burn it dry, it will catch fire immediately. Dunk it in a bowl of water, and try to do the same.

That waste in European and American countries is like the dry cloth, it has a lot of paper that burns easily, and little food and organic residue. India, Bangladesh and other poorer countries are like your wet cloth, it will be very hard to produce electricity by burning them - an issue that is also reflected in the CPCB report. It’s not a geographical issue - Hossain warns - it’s a hidden divide between rich and poor.

Image credit - CSE/To burn or not to burn

Hossain visited the Okhla plant in 2017, and has since stayed in touch with its management, but not once did he get a straight answer on the plant’s power generation. If not enough energy is generated, “they don't make any money and there is a negative environmental effect.” According to the law, the toxic ash residues were supposed to be turned into bricks, but currently just find their way back to the landfill, because making bricks is too expensive.

Pradeep Khandelwal, Chief Engineer with East Delhi Municipal Corporation (EDMC), has been involved in setting up and managing waste to energy facilities in Delhi for over a decade, and acknowledges that waste quality influences how much energy can be produced.

He says that by June 2021 EDMC hopes to have a system in place compelling people to segregate their waste or face penalties. With the new system, organic waste would be composted, “and the plants will receive dry waste only, finally running at maximum efficiency.” If it happens, this upgrade will be five years late, following the 2016 Solid Waste Management Rules that to date remains on paper only.

That’s it for today! If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter and you’d like to read it every week, you can subscribe below, for free. If you want to become a member, don’t miss your early bird discount that is up for grabs until November 1!

Really interesting! I’ve always been perplexed as to why we don’t have a lot of efw plants. In Pune we started segregating waste in 2000, but still no progress on efw. Policy hurdles? Public acceptability?