Welcome to this special edition of Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

A big thank you to my new subscribers, please keep sharing if you like what you read.

A reminder that if you want to become a member, now is the time: you get a 20 percent discount for the next three weeks, and if you are a student, grab your membership with a 60 percent discount. You can also become a founding member by pledging $110, or whatever amount you like (above the annual membership price).

Image credit - Pixabay

The energy world faces unprecedented uncertainties. How long will the pandemic last, and how should governments around the world respond? Is it possible to lift countries out of a disastrous recession while at the same time reducing their climate footprint?

The World Energy Outlook report addresses these questions and more, looking at the lingering impacts of the Covid crisis in the coming decade. Every year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) captures the state of the world’s energy sector in an intimidating tome, dissecting everything from global fuel trends to the use of kerosene in rural homes: it’s the go-to resource for policymakers and businesses to plan their future.

While great explainers about this year’s global picture are already online, I went through the report page by page (you’re welcome) to tease out what’s in it for India.

Overview

The world is moving towards a global energy transition, with a number of countries having already committed to aggressive decarbonisation.

In all scenarios charted by IEA, solar is firmly “at the centre of this new constellation of electricity generation” thanks to mature technologies, falling prices and supportive policies all over the world. Based on the existing policies, renewable energy will meet 80 percent of the growth in energy demand by 2030.

But while the Covid crisis may be an opportunity for richer nations to embrace a net-zero target (so far the EU, UK, China, New Zealand among others), the global picture is more complex. For emerging economies such as India, the consequences of the lockdown may disrupt efforts to grow sustainably.

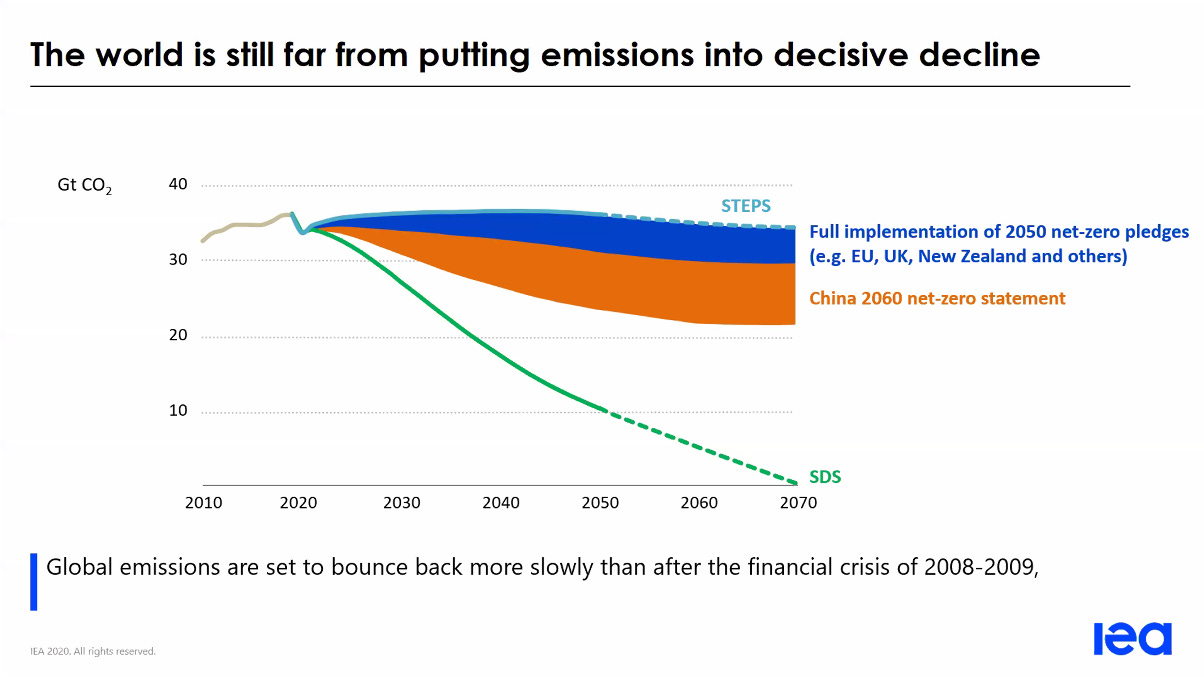

China and other countries making a dent in the progression of carbon emissions. Image credit - World Energy Outlook

Emission patterns

According to IEA’s experts, global energy demand is set to drop by 5 percent in 2020, CO2 emissions from the energy sector will decline by 7 percent, and energy investment by 18 percent. While oil and coal use fall by 8 and 7 percent respectively, the contribution of renewables rises slightly.

Why it matters: We saw a similar pattern in India during lockdown!

A 2.4 gigatonnes (Gt) decline takes annual CO2 emissions back to levels recorded in 2010. However methane, another powerful greenhouse gas, may not be declining as spectacularly.

Why it matters: India has a methane problem we never talk about

Within the next 20 years, India is expected to become the largest market for utility-scale battery storage, following the expansion of investments in solar PV. More people owning air conditioned homes and consuming more will also spur a fast growth in electricity demand in India (as well as in Southeast Asia and Africa).

While this is good news, the analysts caution that energy capacity is only one side of the story. Electricity grids are the most vulnerable link of the chain. Problems such as the sorry state of utilities in some emerging economies have worsened as a result of the crisis and, the authors warn, could have serious consequences for energy security and reliable power supply.

Why it matters: In India, the chronic financial insecurity faced by the public may have a chilling effect on energy investors - including renewable developers.

Electricity

Indians use less than 30 percent of the global average electricity levels, about 850 kilowatt hours (kWh) per capita a year. The economy is booming and this in theory should change rapidly, but electricity consumption has been going down for the past two years, well before Covid struck.

This decline has affected coal in particular, and generation is now on track to fall below 70 percent of the energy mix for the first time in a decade. With the current policies in place, IEA estimates that coal fired capacity will plateau by 2025, mainly due to the aggressive investments in renewable capacity. The emphasis on solar, in a country where energy demand tends to peak in the evening, means that there is huge scope for storage development, which ultimately is expected to surpass coal capacity.

Why it matters: Despite these unsurprising projections, the Indian government is still scrambling to salvage the coal industry.

Image credit - World Energy Outlook

Energy Storage

Utility scale battery storage is expected to grow fast: IEA estimates that with the current policies in place, the sector will increase 20-fold between 2019 and 2030, with 130GW of installed batteries within the next decade. India is set to become the world’s largest market for battery storage, complementing its growing PV infrastructure.

Why it matters: Batteries and other forms of storage are needed to ensure grid flexibility and greater renewable integration.

Fuels

A fast economic growth in India, China and the Asia Pacific region at large means that demand for all fuels will go up in the next 10 years. Renewables will see the fastest growth, but demand for natural gas, oil and coal is also expected to rise.

Energy demand in India will grow by an average 2.6 percent annually, with coal accounting for nearly 30 percent of this growth. Oil demand growth also sits at 30 percent to 2030, 4 percent less than previously projected because more people will choose rickshaws and motorbikes instead of expensive cars.

Solid biomass remains the main source of energy for many in India, mostly used for cooking. Combined with inefficient cookstoves, biomass still leads every year to around 2.5 million premature deaths globally due to indoor pollution.

Image credit - World Energy Outlook

Cooling

Simple actions such as washing clothes in cool water, line drying instead of using a drying machine, and keeping your room temperature just one degree higher when using an air conditioner can make a big difference. For example, global emissions due to the current indoor cooling demand would decrease by 7 percent for each 1C increase in the desired room temperature.

Why it matters: India doesn’t need to reverse these consumption patterns - very few people use a tumble drier and only a tiny percentage currently has air conditioning at home, but as the country develops consumer behaviours will determine the cooling sector’s impact.

Clean Air

By 2030, levels of pollutants such as microparticles PM2.5, nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide will decline by 10 to 20 percent globally, however nearly a billion more people will live in cities and breathe polluted air. Around half a million additional premature deaths a year will be mostly concentrated in Asia, including India and China. Around 60 percent of these deaths will be associated with outdoor air pollution.

The IEA has an optimistic take on this problem. Under its Sustainable Development Scenario it is possible to drastically reduce PM2.5 emissions from the energy sector. According to new analysis, many cities would reduce their PM2.5 levels by 45-65 percent by 2030, which would result in cleaner skies than the ones we enjoyed during lockdown (without economic downturn!).

However, this scenario is not based on existing policies - the analysts here set a goal and work their way back to see what would be needed to achieve it. So this outcome is technically possible, but currently very unlikely.

Delayed recovery

What happens if the pandemic doesn’t go away? Imagine we are still in and out of lockdown well into 2021 - IEA has a whole new scenario for that. Globally, a prolonged health crisis would lead to lower energy production and consumption across most regions. India and China, with their huge energy needs, will be affected particularly badly. India remains a global driver of energy demand growth, but the trend will be much slower - due to fewer people moving to the city and having a smaller income.

Battery storage is a silver lining: as renewables keep growing, so does storage infrastructure which provides much needed flexibility to the grid. In this scenario, compared to one in which the pandemic is over soon, battery systems would be only 5 percent lower.

Why it matters: India is particularly vulnerable to a prolonged pandemic, but has an opportunity in storage investment, which would serve its thirst for renewable integration.

That’s it for today! If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter and you’d like to read it every week, you can subscribe below, for free. If you want to become a member, don’t miss your early bird discount that is up for grabs until November 1!